|

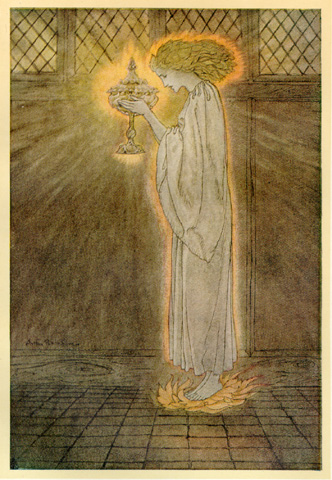

| How at the Castle of Corbin a Maiden Bare in the Sangreal and Foretold the Achievements of Galahad: illustration by Arthur Rackham, 1917 Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/19/Sangreal.jpg |

The most important symbol in all Fisher King legends is

the Holy Grail, usually described as a sacred cup which holds the blood of

Christ. However, the original French

word for the Grail, the sangraal,

also could be interpreted as a stone, which is also religiously significant

because of the symbol of the foundation of the Christian. Since the Grail is an important symbol, it

too must play a significant role in The

Waste Land’s thematic exposition, not as a nourishing symbol of a cup, but

as the unwieldy stone which provides refuge.

In its most popularly recognized form of a cup or

chalice, the Holy Grail is not ostensibly in the poem. Aside from the mention of “vials of ivory and

coloured glass” (746) and empty bottles (749), there is little mention

of containers, and no reference to anything resembling a chalice. The absence of such imagery is perhaps

significant, as the only other option of the Grail imagery is as a stone. This difference is drastic in that the

connotation for a chalice is of healing, coolness, and the quenching of thirst,

whereas a stone brings to mind hard, dry desolation without anything to

alleviate thirst.

The Grail as a stone is represented as the red rock: “There

is a shadow under this red rock / (Come in under the shadow of this red rock)”

(744), which offers refuge from the destitution of the Waste Land. This symbolism of rock and stone recurs

throughout The Waste Land, often

mentioned in conjunction with colors. In

“A Game of Chess,” for example, the room described in the opening contains

reflective marble and a ceiling “framed by the coloured stone” (746),

harkening back to the red rock previously mentioned in the poem.

In the first section of The Waste Land, the rock is a place of refuge, but it also illustrates

the conflict between the Waste Land’s harsh atmosphere and its persistent hope

for relief. Although it offers shelter

from the scorching sun via its shadow, the Rock is stationary, and cannot make

any active move to help the traveler.

Like the Rock, the Grail offers relief, but only if one finds it; the

Grail is an object and therefore cannot take any action of its own volition.

The Grail, in the image of the rock in the Waste Land, is

defined by its desolate, negative surroundings.

However, it is the main positive force in the poem, and offers redemption in even the direst of circumstances. Just as the Rock represents shelter from the

harsh natural elements, the Grail represents the hope of redemption from

suffering, from uselessness, and chaos.

|

| The Attainment: The Vision of the Holy Grail to Sir Galahad, Sir Bors, and Sir Perceval (also known as The Achievement of the Grail or The Achievement of Sir Galahad, accompanied by Sir Bors, and Sir Perceval). , Number 6 of the Holy Grail tapestries woven by Morris & Co. 1891-94 for Stanmore Hall. This version woven by Morris & Co. for Lawrence Hodson of Compton Hall 1895-96. Wool and silk on cotton warp. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. Source: http://www.onlineuniversities.com/wp-content/uploads/quest%20for%20the%20holy%20grail.jpg |

T. S. Eliot

admits in his footnotes that “not only the title, but the plan and a good deal

of the incidental symbolism of the poem were suggested by Miss Jessie L.

Weston’s book on the Grail legend: From

Ritual to Romance” (756). Eliot’s

allusions to Weston’s anthropological study of the Grail legend is appropriate

considering the book relates it to fertility rituals, and traces recurrent

symbols a wounded god or king throughout several ancient and multicultural

mythologies. In From Ritual to

Romance, Weston explores not only

the possible meanings of the Fisher King myth, but also connects it to such seemingly

unrelated material as Tarot cards, which also would feature prominently in

Eliot’s poem.

Using anthropology to trace certain recurring humanist

themes is something else Eliot acquires from Weston’s book. The

Waste Land is acutely self-conscious of its place in history—of its

perpetuation of traditional and innovation of modern literature. However, Eliot’s use of generally human

concepts like interpersonal relationships and the search for redemption confirm

that he was not only writing in homage of previous epics and classic poets, but

that he was also writing something that held relevance in modern

civilization. If anything, Eliot uses

the traditional allusions as scaffolding on which to structure more existential

themes.

The use of traditional literature also affects the

structure—or the seeming lack of it—to the poem. Arthurian romances were often so meticulously

ordered in plot that they are justly described as cyclical. However, the Grail legend “resists the

ordering of plot. The ‘meanings’ are

always overflowing the narrative and overwhelming the design,” and this idea

that the themes take priority before poetic structure is perhaps one that Eliot

used in writing The Waste Land. Repeated words and phrases like “rock,” “the

violet,” and “water” are used as signposts to guide the reader to Eliot’s main

themes of barrenness, repentance, and deliverance, as well as plot out a

modernist retelling of the Fisher King legend.

Although the Grail legend is a significant plot in The Waste Land, Eliot’s use of

additional connotations from such works as Dante’s Inferno, Shakespearean plays, and even the Bible, supply more

thematic information for the reader to use in understanding the poem as a

whole. References outside of European

literature show that the themes in the poem transcend time and culture, as the

issue of human mortality confronted in this genre is recurrent throughout the

history of global literature.

Independently, The

Waste Land is a masterpiece in its own right. But as a work drawing on history while moving

toward the future, it takes part in a community of literature which gives the

poem a sort of comprehensive structure.

Eliot uses what otherwise would be considered a chaotic jumble of

abstract quotes and allusions from various forms of literature to create a sort

of verbal mosaic that, when seen holistically, illustrates his themes of

humanity, religion, life and death. Even

when personal inner-conflict is resolved, the quest for universal peace for all

humanity continues. The poem ends with

the continued battle between the desire for order in the universe, and

surrendering to the inherent chaos of human life.

The conclusion of The

Waste Land is the source of several critical controversies. One such controversy regarding Eliot’s use of

the Fisher King myth is whether the protagonist ever succeeds in his

quest. While some scholars believe that

the poem’s end is one of marginal hope for deliverance, others argue that the

poem ends in true Grail romance fashion, with the Quester achieving his goal

and the Fisher King and his land being restored.

The rationale behind the argument that the Quester

ultimately fails is that there is a tone of submissive despair in The Waste Land’s conclusion. The hopelessness in “A Game of Chess” which

is expressed by the nightingale who “Filled all the desert with inviolable

voice / And still she cried, and still the world pursues” (746). The passive acceptance in the face of failure

echoes even in the poem’s conclusion: “I sat upon the shore / Fishing, with the

arid plain behind me / Shall I at least set my lands in order?” (756).

This perspective is seemingly supported by the following

lines, which are frenetic and nonsensical.

However, this interpretation does not account for the last word of the

poem, shanti, which Eliot translates

as “the Peace that passeth understanding” (760). Although passive in the sense that the

protagonist seemingly is at peace, there is no indication that he merely accepts

his existence in the Waste Land.

The other interpretation of The Waste Land’s conclusion is far more optimistic, and assumes the

invariable success of the Quester that is the traditional conclusion among

medieval romance cycles. The proponents

of this interpretation admit that the scenes reminiscent of the Chapel Perilous

lead the reader to believe that the quest will be in vain, but then “a damp

gust / Bringing rain” (755) relieves the Waste Land of its drought. The controversy of whether the Quester

actually succeeds to restore the Waste Land arises because the poem’s complexity

begs to be interpreted in many diverse ways with a variety of methods. The dilemma of the modern mind is how

humanity makes order out of chaos, reviving a seemingly dying culture into a semblance

of its former glories just as the Fisher King and his people desire to do. The Quester discovers the inadequacies of his

own identity, as well as his inherent flaws that cause him to fail. These myths

create the sense that the existential problems of modern civilization are not

particular to modern civilization at all, but are part of a universal issue

that transcends culture, religion, and time.

Although the deliverance of the Waste Land is precarious, its ultimate

message is one of hope, because as long as life persists, redemption can never

come too late.

Thanks, I really appreciate your treatment of The Waste Land. How pleasant to meet Mr. Eliot/Whether his gaze be downward or up!

ReplyDeleteVery well written

ReplyDeleteExcellent posts, many thanks.

ReplyDelete